Moses Delivering His Ten Commandments – David Courlander – Smithsonian Art Museum

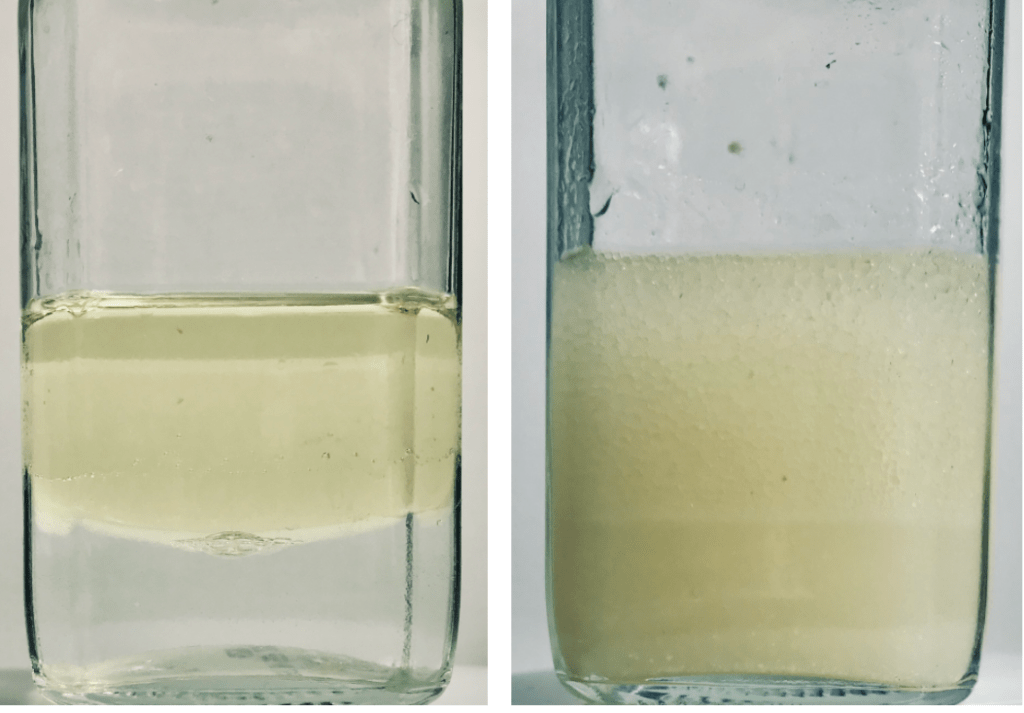

The popularity and influence of the classic faiths are on the wane. Pew surveys have shown that between 1972 and 2020 the number of respondents who answered “none” in response to being asked their religious affiliation rose from 5% to 30%. In a pair of Pew US Population surveys, the percent of ethnic Jews identifying as also Jewish by religion fell from 95% in 2001 to 78% in 2019. Another pair of Pew surveys showed that in 2014, 87.6 % of adults who had been raised in Christian households continued to identify as Christians. Recent Pew studies, however, show the current retention rate to be closer to 67% . Similar declines have been observed in most Western countries and the Roman Catholic church.

Environmental groups, on the other hand, have been growing. The Sierra club in 1980 had 200,000 members, now there are over a million.The World Wildlife fund was founded in 1980 and now has over 5 million supporters worldwide. The National Resources Defense Council was founded in 1970 and now has 1.5 million members in the U.S.

The elements of those classic faiths evolved millenia ago and have served humankind well. The old testament did a good job steering tribes of ancient peoples towards collective behavior favoring survival. Forbidding murder and covetousness fostered group cohesion and minimized intratribal strife. A stronger tribe was a more successful tribe. About 1000 years later the new testament broadened these prescriptions to make them more relevant to the evolving urban density of the time – fostering altruism and tempering justice with forgiveness.

Those monotheistic faiths arose in a very different cultural and sociological world. The earth’s population was a fraction of today’s billions and vast regions of the earth were virgin wilderness. There was plenty of land to relocate to when natural resources of one area became depleted. The causes of important natural phenomena – thunder, earthquakes, hurricanes and the like were unknown. Life and death had more to do with fate and defense from hostile enemies than with anthropogenic technologic and scientific interventions. An omnipotent, omniscient, invisible external force was the simplest, most efficient way to explain most complex phenomena. Such a singularity, parceling out rewards and punishments depending upon good or bad (read socially beneficial or hostile) behavior played an important role in creating powerful inter-human alliances and communities. Eighteenth century philosopher Voltaire, recognizing the importance of god in maintaining social order, famously wrote “If God does not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.”

Now, almost two millennia after the New Testament was written, we clearly need a new sacred text to guide us around humanity’s newest threats – to become the foundation, if you will, of a new religion, with its own spirituality and a degree of deep nature worship which inspires and rewards meaningful sacrifice and independent evangelism built around Nature. It is hardly histrionic to say that if we are to avert a metaphoric hell on earth we need a new faith based on worship of an Earth Mother – recognizing her role in sustaining us, providing us our daily bread and having miraculous power to forgive and heal the wounds she suffers at our hand. And if we can bring this off, there is a chance that something akin to the Garden of Eden can be restored.

To navigate the climate crisis and biodiversity armageddon, we need an expanded set of widely accepted moral principles, imbued with the force of religion. If Moses’ tablet had been an ipad instead of stone, if he had had access to the modern web, and he understood the threats facing us today, those Ten Commandments would surely look different. And there would probably be more than ten.

The first five in particular need a major overhaul. Get rid of the first – “Thou shall have no other gods before me“ – and replace it with something like: “Recognize the sanctity of all life and its interconnectedness.”

The second, “Thou shalt have no false idols”, would certainly be replaced by something like “Worshiping personal gain of money and power by exploiting earth’s resources is a sin.” The third – “Thou shall not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain” – might be replaced by something like: “The verbs ‘rot’, ‘decay’, ‘dirty’, and‘soil’ must shed their negative connotations and be recontextualized to mean “reincarnated back into the circle of life.” “Remember the Sabbath and keep it holy” would be replaced by something like ”Make every day Earth Day”.

Religious thinkers have spent a good deal of time and thought developing taxonomies of sin. For Catholics, there were mortal and venial sins. For others there are forgivable and unforgivable sins, the seven deadly sins, sins leading to death and not leading to death, etc. Were Moses inclined to get into that morasse, I suspect one of the most serious modern sins would be lies which corporate executives and political leaders tell to mislead consumers about the harm done to the earth by their products. Surely, by this measure, the CEO of Exxon, whose own scientists warned of greenhouse gas causing global warming well before independent academic and government scientists put it on the map, would be condemned to eternal damnation.

Then there would be an appendix of some nitty gritty housekeeping transgressions:“Do not plant non-native species.” “Forgo pesticides and herbicides””Keep fossil fuels in the ground,” “Do not deny Inconvenient Truths.” etc.

Despite the waning relevance of the major religions, any new religion seeking traction in today’s world can learn from the elements supporting those ancient faiths. Commonalities they share include compelling miracles, group rituals, holydays (sic), sacrifice, awe-inspiring places of worship, music, apostles and often a messiah.

Clearly, there is no shortage of nature’s miracles – consider photosynthesis, the genetic code, the origin of life, the Big Bang – the list goes on. As for group rituals, might things like hikes, river cleanups, sit-ins or pipeline protests be possible contenders. And as for holydays, a nature-based religion has a couple of potentials. Arbor day was established in the 1870’s in the US when a tree-loving newspaper promoted the idea and it soon became nationally recognized. Birders have their annual Christmas week bird count. Earth Day was begun in 1970 by Senator Gaylord Nelson after he and other early environment protectors witnessed a major oil spill off the California coast. Since then it has become a worldwide event celebrated or recognized in over 180 countries.

In addition to the dramatic blood sacrifices of the past, modern practitioners of the ancient faiths sacrifice in a variety of ways. Many Catholics flagellate themselves and wear hair shirts each year. Mormons are expected to tithe ten percent of their income annually and as young adults, many give up a year of their lives proselytizing. Muslims spend 10 to 15 minutes five times each day kneeling in prayer. The Twelver Shia Islam community members forcefully beat their chest, often in public. All identify certain times for fasting and abstinence. All are sustained by material sacrifice on the part of believers. Meanwhile, the best most nature worshippers can do is write an occasional letter to their senator or join one or two conservation non-profits for 25 or 50 dollars a year. What will it take for Nature to inspire the same kind of power and passion that the organized religions of the world have been able to create? Certainly, turning climate change around and making room for more biodiversity and less convenience are going to require lots of sacrifice – which may, paradoxically, even become a widely recognized bona fide virtue rather than a mere burden, as it is viewed by many today.

As for awe-inspiring places of worship, the natural world has plenty. Some have almost universal appeal – watching a sunrise, standing at the foot of a giant sequoia, walking on a lonely beach, any spot free from light pollution from which one can look up at the milky way on a moonless night.

And how about music? One could argue that it was religion which inspired music rather than the other way ‘round but the association is a strong one. Jews have their cantors, Christians their choruses and choirs. Islam forbids instrumental music but has a tradition of a cappella religious works. And of course some of Western civilization’s most moving and long-lived music is associated with Christianity and much of it was even sponsored by the church. Environmentalism is not a desert in this regard. Mahler’s Symphony #3 (about which the composer himself says in a letter to the soprano, Anna von Mildenburg, “In it the whole of nature finds a voice” ) probably sits at the top of the canon. Paul Winter’s haunting music based on whale songs is not far behind. Dvorak’s” In Nature’s Realm”, Christopher Tin’s The Lost Birds, Andrew Bird’s “Rare Birds”, Both Copeland’s ” Nature Overture” and “Appalachian Spring” and even Ben Mirin’s beatboxing all would work as inspiring embellishments in a Church of Nature service.

And just as major religions have their charismatic apostles and “prophets” with a special role as intermediary between the people and a higher power, there are plenty of candidates for such roles in an earth-inspired faith. Consider Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carlson, John Miuir, EO Wilson, Carl Safina, Al Gore, Robin Wall Kamerer, Reverend Billy Talen or Bill McKibben. One of them might even be elevated to full-fledged messianic status rather than remaining mere apostles. For messiahhood, my vote goes to Greta Thunberg – she is of the right generation and gender to do the job in the 21st century, she is inspiring, and she already has a large following.

Overall, one can make a good argument that the stage has been set for the emergence and explosive growth of a new nature-based religion. The tinder is arranged. The twigs are tented over it. There’s plenty of dried fuel stacked nearby. All that’s needed is the final spark.